“Of all the English Reformers, Bishop Hugh Latimer was the most popular in his time and probably has the greatest place in the affections of posterity. Although a passionate preacher and a zealot for reform, in a day when religious executions were all too common, he completed his three-score years and ten, before sealing his testimony with his blood”

(Harold S. Darby, Hugh Latimer (London: Epworth Press, 1953), p. 7.)

850G Hugh Latimer 1485-1555

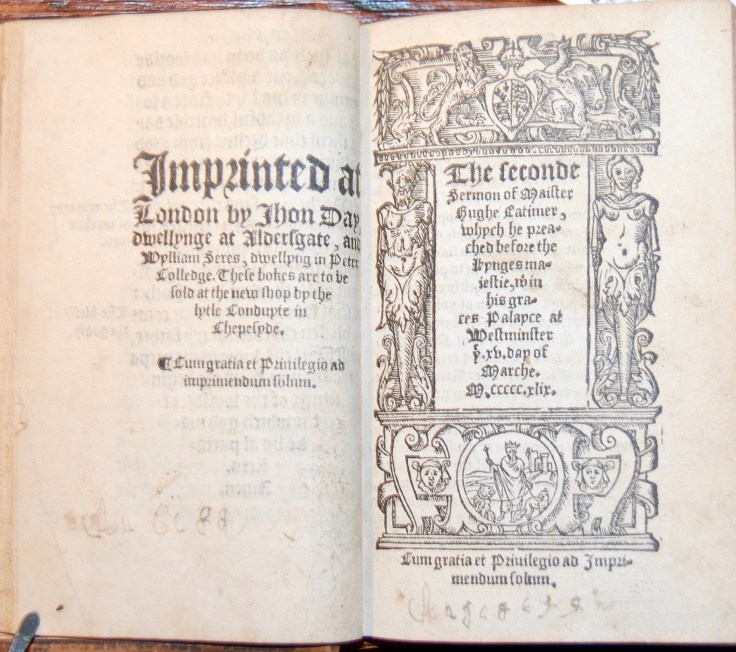

The fyrste Sermon of Mayster Hughe Latimer, whiche he preached before the kynges Maiest. wythin his graces palayce at Westminster M. D. XLIX. the viii. of Marche. (,’,) Cu gratia et Privilegio ad imprimendum solum.

[bound with]

The seconde Sermon of Maister Hughe Latimer, whych he preached before the Kynges maiestie, iv in his graces Palayce at Westminister y. xv. day of Marche. M. ccccc.xlix. Cum gratia et Privilegio ad Imprimendum solum.

[London: by Jhon Day, dwellynge at Aldergate, and Wylliam Seres, dwellyng in Peter Colledge, 1549] $14,200

Octavo 137 x 88 mm A-D8, A-Y8, Aa-Ee8 (Lacking Ee7 and 8, undoubtedly blank.) First editions, each of the two works is one of three or four undated variants, attributed to the year 1549. This copy is bound in nineteenth century calfskin, the hinges starting to crack but holding strong.

Octavo 137 x 88 mm A-D8, A-Y8, Aa-Ee8 (Lacking Ee7 and 8, undoubtedly blank.) First editions, each of the two works is one of three or four undated variants, attributed to the year 1549. This copy is bound in nineteenth century calfskin, the hinges starting to crack but holding strong.

The Encyclopedia Britannica calls Hugh Latimer’s sermons, “classics of their kind. Vivid, racy, terse in expression; profound in religious feeling, sagacious in their advice on human conduct. To the historical student they are of great value as a mirror of the social and political life of the period.”

The Encyclopedia Britannica calls Hugh Latimer’s sermons, “classics of their kind. Vivid, racy, terse in expression; profound in religious feeling, sagacious in their advice on human conduct. To the historical student they are of great value as a mirror of the social and political life of the period.”

“All things which are written, are written for our erudition and knowledge. All things that are written in God’s book, in the Bible book, in the book of the Holy Scripture, are written to be our doctrine.” (from Hugh Latimer’s Sermon of the Plow)

“This was the first of Latimer’s famous Lenten sermons on the duty of restoring stolen goods which resulted in the receipt of considerable sums of ‘conscience money.’” (Phorzimer Catalogue)“The seven sermons which he preached before the king in the following Lent are a curious combination of moral fervor and political partisanship, eloquently denouncing a host of current abuses, and paying the warmest tribute to the government of Somerset.” (DNB)

STC 15270.7; STC 15274.7; Pforzheimer #581 and 582; McKerrow & Ferguson 64.

FROM :

Article reprinted from Cross†Way Issues Winter 1994, Spring 1995, Spring 1996, Summer 1996 & Autumn 1996 (Nos. 55, 56 60, 61 & 62)

(C)opyright Church Society; material may be used for non-profit purposes provided that the source is acknowledged and the text is not altered.

HUGH LATIMER – APOSTOLIC PREACHER. By David Streater.:

“With the accession of Edward VI at the beginning of 1547, the danger to Latimer’s life receded and he was released from the Tower of London under a general pardon. He returned to preaching and as Darby says in his book, Hugh Latimer (1953):-

Latimer’s fame is most secure as a preacher. It was in that way that he served best in the days of Henry VIII: it was almost the only way that he served during the short reign of his son. The six years gave him his fullness of opportunity to follow his natural bent.

It was during these years that the First Prayer Book of 1549 and the Second, more Protestant, Prayer Book of 1552 were drawn up with the Forty Two Articles and the First Book of Homilies. With such a programme of reform, it was clear that Latimer would be the natural choice to return to

the See of Worcester. He was invited to do so but he declined the appointment on the ground of age and infirmity. This was accepted, and as preaching was his high calling, he preached extensively before the young king. Most of our knowledge of his sermons dates from this period of his ministry. He became a champion, not only of the spoken word, but of the Word preached directly to the present congregation. It was a word relevant to the condition of the nation as a whole.

His earlier convocation sermon which had attacked the lethargy and worldliness of the clergy had won Latimer the respect of the nation. His refusal of high office and the wealth which went with it gained their hearts. It would be true to say that no other English preacher has ever been held in such high esteem, including the Wesleys and George Whitefield, as well as Charles Spurgeon. It would also be true to say that no other preacher has ever accomplished as much good in the life of the nation. The records of the State Paper Office and British Museum bear out this testimony. But Latimer was now ageing and after Lent 1550, he resigned as the King’s preacher and he returned to his home country, his beloved Midland Counties, continuing to preach from Lincolnshire to Warwickshire.”

Hugh Latimer preaching to King Edward VI of England, a woodcut in John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, better known as Foxe’s English Martyrs. By the time this book was published in 1563, Edward VI was revered as a pious patron of the English Reformation, a new Josiah who loved nothing better than to hear sermons, during which he often took notes. He is depicted here listening from a gallery to a sermon by Bishop Hugh Latimer, who, along with Thomas Cranmer and Nicholas Ridley, was a key figure in the development of Protestantism in Edward’s reign and, like them, a martyr under Edward’s Catholic successor Queen Mary I. Historian Diarmaid MacCulloch stresses the accuracy of this image of Edward, though fellow historian Jennifer Loach cautions against too ready an acceptance of the portrayal of Edward by Reformation propagandists such as Foxe, who called Edward a “godly imp”. The pulpit in the Privy Garden at the Palace of Whitehall had been built by Henry VIII in an enclosure which continued to be used for animal-baiting and wrestling. The king’s pulpit became the most fashionable preaching place in London, provoking Latimer to complain: “Surely it is an ill misorder that folk shall be walking up and down in the sermon-time, as I have seen in the place this Lent: and there shall be such huzzing and buzzing in the preacher’s ear that it maketh him oftentimes to forget his matter”. (References: Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Boy King: Edward VI and the Protestant Reformation, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002, pp. 21–25, 107; Jennifer Loach, Edward VI, New Haven (CT): Yale University Press, 1999, pp. 180–81.) & Chris Skidmore, Edward VI: The Lost King of England, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2007, ISBN 9780297846499.

Leave a Reply