523J Thomas Cooper 1517-1594

Thesaurus Lingvae Romanae & Britannicae, tam accurate congestus, ut nihil pene in eo desyderari possit, quod vel Latine complectatur amplissimus Stephani Thesaurus, vel Anglice, toties aucta Eliotae Bibliotheca: opera & industria Thomae Cooperi Magdalenesis. Quid fructus ex hoc Thesauro studiosi possint excerpere, & quam rationem secutus author sit in Vocabulorum interpretatione & dispositione, post epistolam demonstratur. Accessit Dictionarium Historicum & poeticum propria vocabula Virorum, Mulierum, Sectarum, Populorum, Orbium, Montium, & caeterorum locorum complectens, & in his iucundissimas & omnium cognitione dignissimas historiae.

Impressum Londini : [by Henry Denham], 1584. $2,500

Folio: 38 x 20 cm Signatures. ¶4, A6 B-Y6, Aa-Yy6, Aaa-Yyy6, Aaaa-Yyyy6, Aaaaa-Yyyyy6, Aaaaaa1-Yyyyyy6, Aaaaaaa-Vvvvvv6(Dictionarium Historicum begins on Aaaaaaa-Mmmmmmm5 of 6, Lacking final blank.

Cooper, in addition to his controversial and historical works, (he completed Lanquet’s Chronicle and became embroiled in two of the greatest controversies of ecclesiastical polity of the sixteenth century in England: the Jewel/Harding exchanges and the “Martin Marprelate” controversy) his expanded and corrected edition of Eliot’s dictionary appeared in 1552 and 1559. He then went to work on what the DNB calls “his greatest literary work” the present “Thesaurus Lingvae Romanae & Britannicae” According to the DNB this work “delighted Queen Elizabeth so much that she expressed her determination to promote the author as far as lay in her power.”

STC (2nd ed.), 5688

§

512J John Speed. (1552-1629)

The (First word of title is xylographic.) Historie of Great Brittaine under the Conquests of the Romans, Saxons, Danes and Normans. Their Originals, Manners, Habits, VVarres, Coines, and Seales: with the Successions, Lives, Acts, and Issues of the ENGLISH MONARCHS, from Jullius Caesar, to our most gracious Soveraigne KING IAMES of famous Memorie.

London: printed by Iohn Davvson [and Thomas Cotes], for George Hvmble, and are to be sold in Popes-head Pallace, at the signe of the White Horse. Cum priuilegio, 1632. price $2,850

Large Folio, 34 x 22 cm. signatures: ¶⁶ A-B6-Aa-Hh⁶ Ii⁴, Kk-Aaaa-Ssss⁶ Tttt⁴ Vvvv-Zzzz⁶ Aaaaa6 Bbbbb-Qqqqq⁶, Xxxxx-Yyyyy6 Zzzzz4. (complete) Third edition. Many woodcuts appear throughout the text of coins, seals, Celtic and Roman artifacts, arms, family trees, uncivilized and civilized Britons, and more. This copy has a few minor stains, with large margins. This copy is in good shape, with ample margins. This copy has its original seventeenth century calf boards, which has been re-backed with title gilt on spine, with later end papers. The engraved title page signed ‘S. Savery’ sculpt. and vignette engravings and woodcuts throughout are by Christoph Schweitzer.

Speed’s History of Britain begins with the Ancient Britons, and describes their dress, habits, religion, and lifestyle. One notable illustration depicts these `Ancient Britons,’ naked but for arms, torques, and belts, and completely tattooed. The male Briton holds a severed head by the hair. Speed then moves on to describe Christianity’s arrival in Britain, again enhancing the text with woodcuts of artifacts, seals, family trees, and crests that date from this period. Then Speed describes the Roman period in British history, and illustrates Roman coins and artifacts. The next two sections give the royal history of Saxons and Danes in Britain. The final section brings the history to Speed’s own time, with its account of the English monarchy. The woodcuts continue throughout. In the last few sections, Speed gives lists of the Hospitals in England and Wales, and the Religious Houses and Colleges. Charts are also printed for Oxford and Cambridge Universities that for each college report its original founders, students, the year of its establishment, its benefactors, gifts, in which King’s reign they were given, and the names of early residents.

Speed, Stowe, and Camden laid the foundations of English chronicle writing. Speed was responsible for elevating the tone of Stowe by utilizing the science of Camden sewing a complicated and dense version of the story of the history of Great Britain.

“Whereas Speed requires fifty-four chapters in Book VI to deal with Roman Britain and forty-four in Book VII to relate the history of the Saxons, in Book VIII he devotes only seven chapters to the Danes. But the gigantic summit of the work is Book IX, entitled ‘The Succession of England’s Monarchs’ from William the Conqueror to Elizabeth. Its twenty-four chapters and almost five hundred pages make the eleven pages of Book X, on the reign of James I, appear to be a tiny coda. The ‘Summary Conclusion of the Whole’ is a ‘scanted epitome’ where, as Speed explains, the reader may ‘ascend these five national stories already finished’ and thus be led into the sixth ‘now most happily begun.’” (Quoted from Herschel Baker’s The Later Renaissance in England, pages 841-842.)

STC 23049 (A variant of the 1631 edition)

<V>

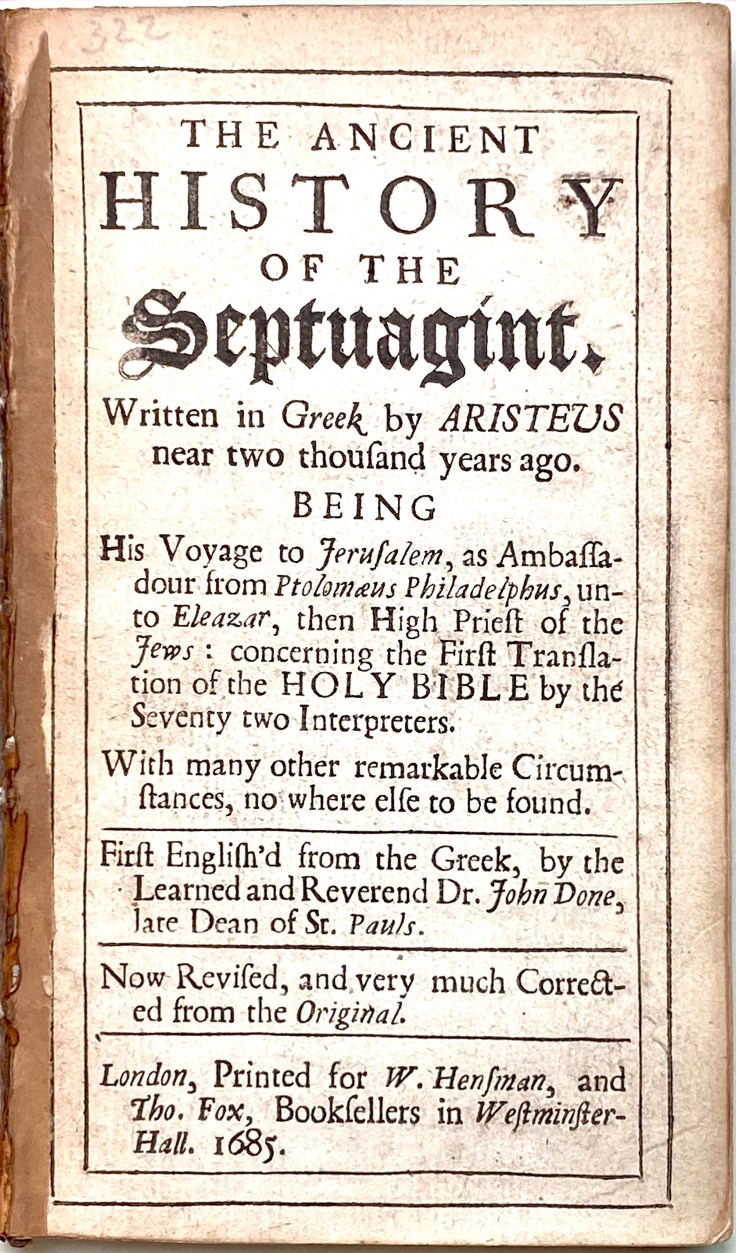

Donne, John, ; 1572-1631. (Both the account and the author are fictitious.)

THE ANCIENT HISTORY OF THE SEPTUAGINT. WRITTEN IN GREEK BY ARISTEUS NEAR TWO THOUSAND YEARS AGO. BEING HIS VOYAGE TO JERUSALEM, AS AMBASSADOUR FROM PTOLOMAEUS PHILADELPHUS, UNTO ELEAZAR, THEN HIGH PRIEST OF THE JEWS: CONCERNING THE FIRST TRANSLATION OF THE HOLY BIBLE BY THE SEVENTY TWO INTERPRETERS. WITH MANY OTHER REMARKABLE CIRCUMSTANCES, NO WHERE ELSE TO BE FOUND. FIRST ENGLISH’D FROM THE GREEK, BY THE LEARNED AND REVEREND DR. JOHN DONE, LATE DEAN OF ST. PAULS. NOW REVISED, AND VERY MUCH CORRECTED

Imprint: London : Printed For W. Hensman, And Tho. Fox, 1685 $1,800

STC (2nd ed.), 18038

Duodecimo 15x 8.5 cm. Signatures: A-I¹².. Contemporary calf.

John Donne “was an English poet and cleric in the Church of England. He is considered the pre-eminent representative of the metaphysical poets. His works are noted for their strong, sensual style and include sonnets, love poems, religious poems, Latin translations, epigrams, elegies, songs, satires and sermons” (Wikipedia 2017) .Tat Donne’s name was used in relation to this book, twice in 1633 and here is curious. The Septuagint “is a translation of the Hebrew Bible and some related texts into Koine Greek. As the primary Greek translation of the Old Testament, it is also called the Greek Old Testament” (Wikipedia 2017) . The Letter of Aristeas “or Letter to Philocrates is a Hellenistic work of the 2nd century BCE, assigned by Biblical scholars to the Pseudepigrapha. Josephus who paraphrases about two-fifths of the letter, ascribes it to Aristeas and to have been written to a certain Philocrates, describing the Greek translation of the Hebrew Law by seventy-two interpreters sent into Egypt from Jerusalem at the request of the librarian of Alexandria, resulting in the Septuagint translation. Though some have argued that its story of the creation of the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible is fictitious, it is the earliest text to mention the Library of Alexandria” (Wikipedia 2017) . According to OCLC, both the account and the author are fictitious. “Aristeus, the near Kinsman and Friend of King Ptolomeus Philadelphus, is named by St. Hierom Ptolomei Hyperaspistes, the Shield of the King, or he that defends the King with his Shield, or Bearer of the Shield Royal, which seems to me, that he held some such place about the King his Master, as we call at this Day the Great Esquire of the Kings Body, he was the Principal Sollicitor for the Liberty of the Jews, that then were held Slaves throughout all the Dominions of Ptolomy; for he made the first request for them, and he obtained it. ” Other titles: Letter of Aristeas, History of Aristeus. [Wing A3682] SUBJECT(S) : Bible, Old Testament, Greek-Versions-Septuagint-Early works to 1800. OCLC lists 14 holdings worldwide. Minimal staining and toning. Loose leather binding with heavy wear. Minimal pencil markings that do not affect text. Internally Very good condition. (SPEC-44-7), Nj1 208-210. Wing (2nd ed., 1994),; A3682; Arber’s Term Cat. II,; 161

:.:+:.:

The Sieur de Parc = Charles Sorel., 1602?-1674.

Vraye histoire comique de Francion. English

The comical history of Francion. Satyrically exposing folly and vice, in variety of humours and adventures. Written in French by the Sieur de Parc, and translated by several hands, and Adapted to the Humour of the present Age.

London: Printed for R. Wellington, 1703. $1,500

Octavo x cm. Signatures: A⁴ B-O⁸ P⁴ Q²; 2A-2G⁸ 2H⁴ 2I-2P⁸ 2Q⁴; 3A-3H⁸ 3I⁵ (2I2, 2I4 missigned 2K2, 2K4) A different translation from that published in 1655 1st. First Edition of this translation. Modern brown cloth, gilt lettering on spine. In three sections, Part I, with separate paging and register: Book 1-6, book 7-10, book 11-12. Section 1, p. 219 misprinted as 119. Section 2 paging omits numbers 90-99; repeats page numbers 121, 124-130, 138-139, out of order.

“Written in French by the Sieur de Parc and translated by several hands, and adapted to the humour of the present age.” , Sorel, “was historiographer of France [in 1635]. He wrote on science, history and religion, but is only remembered for his novels. He tried to destroy the vogue for the pastoral romance by writing a novel of adventure, the Histoire comique de Francion (first edition in seven volumes, 1623; second edition in twelve volumes, 1633).§ The episodical adventures of Francion found many readers, who nevertheless kept their admiration for Honoré d’Urfé’s L’Astrée, which it was intended to ridicule.” (Wikipedia) OCLC: 30941570, \Some edge wear on cover corners and spine. Private blind stamps to title, final leaves, and rear endpages. Last 2 leaves rubbed with clear tape at inner gutter. Lacking final leaf of ads at rear for books from R. Wellington at rear (2 of 3 leaves of ads are present). A few pages have some minor edgewear. Previous owner’s name on title page.

258J Richard Montague

A gagg for the new Gospell? No: a nevv gagg for an old goose. VVho would needes vndertake to stop all Protestants mouths for euer, with 276. places out of their owne English Bibles. Or an ansvvere to a late abridger of controuersies, and belyar of the Protestants doctrine. By Richard Mountagu. Published by avthoritie

London : Printed by Thomas Snodham for Matthew Lownes and William Barret, 1624. Price $950

Quarto 17 x 13 cm. signatures: π⁴ ¥⁴ ¶-¶¶¶⁴ A⁴(±A4) B-Y⁴ Z², Aa-Tt⁴. First and only edition, this copy is bound in full contemporary calf with the top hinge restored expertly.

“Montague was a theological polemicist whose attempt to seek a middle road between Roman Catholic and Calvinist extremes brought a threat of impeachment from his bishopric by Parliament. Chaplain to King James I, he became archdeacon of Hereford in 1617.

About 1619 Montagu came into conflict with Roman Catholics in his parish. Exchanging polemical repartee with Matthew Kellison, who attacked him in the pamphlet The Gagge of the Reformed Gospell (1623), he replied with A Gagg for the New Gospell? No. A New Gagg for an Old Goose (1624). The same year his Immediate Addresse unto God Alone antagonized the Puritans, who appealed to the House of Commons. Protected by James I, he issued Appello Caesarem (1625; “I Appeal to Caesar”), a defense against the divergent charges against him of popery and of Arminianism, a system of Protestant belief that departed from strict Calvinist doctrines.

Although Montagu was frequently called before Parliament and conferences of bishops, he was saved from retribution by his influence at court and with Archbishop William Laud, whose views about the catholicity of the English church he shared. Despite opposition, Montagu was appointed bishop of Chichester in 1628 and of Norwich in 1638. His works include The Acts and Monuments of the Church Before Christ Incarnate (1642).” EB

∞

187J Thomas, Archbishop of Canterbury Cranmer (1489-1556)

A Defence of The True and Catholike doctrine of the sacrament of the body and bloud of our sauiour Christ, with a confutation of sundry errors concernyng the same, grounded and stablished vpon Goddes holy woorde, & approued by ye consent of the moste auncient doctors of the Churche. Made by the moste Reuerende father in God Thomas Archebyshop of Canterbury, Primate of all Englande and Metropolitane.

Imprynted at London : in Paules Churcheyard, at the signe of the Brasen serpent, by Reynold Wolfe. Cum priuilegio ad imprimendum solum, anno Domini. M. D. L. [1550] $28,000

Quarto 7 x 5 ½ inches [4], 117, [3] leaves Collation: *4, A-Z4, Aa-Gg4 This copy is bound in contemporary, blind-stamped English calf with small medallion portrait rolls. The boards are composed of printer’s waste taken from John Bale’s ” Illustrium Maioris Britanniae Scriptorum” of 1548. The text block is backed with vellum manuscript fragments. A number of blank leaves have been bound in at the beginning of the volume. Internally, this copy is in excellent condition with clean, wide margins. Both the binding and the text are in strictly original condition.

Thomas Cranmer rose to prominence as the architect of the ecclesiastical arguments used to legitimize Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon. For his services in this matter, Henry rewarded Cranmer with the primacy, making him Archbishop of Canterbury in 1533. Cranmer’s subsequent promotion of the English Bible and his central role in the development of the early reformed church “has associated his name more closely, perhaps, than that of any other ecclesiastic with the Reformation in England.” After the death of Henry VIII, Cranmer oversaw and participated in the production of several key texts of the reformed church, including the two Prayer Books of Edward VI (1548, 1552) and the “Forty-two articles of Edward VI” (I553).

“In Cranmer’s response to Gardiner, “A Defence of the True and Catholike doctrine of the sacrament of the body and bloud of our sauiour Christ”, the archbishop offers a semi-official explanation of the Eucharistic theology that lay at the heart of his Prayer Book.

“The ‘Defence’ is divide into five sections, whose polemical architecture was dependent on the relatively brief first section. This set out the nature of the Eucharistic sacrament, centering on a recitation of all the Gospel and Pauline texts that could be considered as referring directly to it. Cranmer took two principal points from these citations. First, when Christ referred to the bread as his body, this was precisely to be understood as a signification of ‘Christ’s own promise and testament’ to the one who truly eats ‘that he is a member of his body, and receiveth the benefits of his passion which he suffered for us upon the cross’; likewise Christ’s description of the wine as his blood was a certificate of his ‘legacy and testament, that he is made partaker of the blood of Christ which was shed for us.’ Secondly, one must understand what was meant by the true eating of Christ’s body: although both good and bad ate bread and drank wine as sacraments, Cranmer emphasized in a classic expression of the ‘manducatio impiorum’ that ‘none eateth of the body of Christ and drinketh his blood, but they have eternal life’, and that this could not include the wicked.

Cranmer went on in a now celebrated passage to the heart of his quarrel with the old world of devotion:

‘Many corrupt weeds be plucked up…But what availeth it to take away beads, pardons, pilgrimages and such other like popery, so long as two chief roots remain unpulled?…

The very body of the tree, or rather the roots of the weeds, is the popish doctrine of transubstantiation, of the real presence of Christ’s flesh and blood in the sacrament of the altar (as they call it), and of the sacrifice and oblation of Christ made by the priest for the salvation of the quick and the dead. Which roots, if they be suffered to grow in the Lord’s vineyard, they will spread all the ground again with the old errors and superstitions.’

“This was the purpose of his book, and his duty and calling as Primate of all England: ‘to cut down this tree, and to pluck up the weeds and plants by the roots.’ Yet there is a contrast in the Preface (and in the ‘Defence’ as a whole) with the unpleasing monotony of Cranmer’s answer to the western rebels of 1549: here, there is an obvious and urgent pastoral concern for the people entrusted to his care. He called, ‘all that profess Christ, that they flee far from Babylon’. ‘Hearken to Christ, give ear unto his words, which shall lead you the right way unto everlasting life.’ This was the language of the Prayer Book given a revolutionary edge.” (Diarmaid MacCulloch, “Thomas Cranmer, A Life” pp. 461-469)

When Mary Stuart assumed the throne in 1553, Cranmer was charged with both treason and heresy (for his support of Lady Jane Grey and an unpublished declaration he had written against the mass.) In March, 1554, Cranmer, along with Latimer and Ridley, was tried as a heretic at Oxford. In early 1556, Cranmer subscribed to several “recantations”., when Cranmer was asked to repeat his recantations at St. Mary’s Church on March 21st, he “declared with dignity and emphasis that what he had recently done troubled him more than anything he ever did or said in his whole life; that he renounced and refused all his recantations as things written with his hand, contrary to the truth which he thought in his heart; and that as his hand had offended, his hand should be first burned when he came to the fire.” When Cranmer was put to the stake, “stretching out his arm, he put his right hand into the flame, which he held so steadfast and unmovable, (saving that once with the same hand he wiped his face,) that all men might see his hand burned before his body was touched.”

STC 6002 (with catchwords B4r “des”, S1r “before”.) Title page border: McKerrow & Ferguson 73; Printer’s device: McKerrow 119. References: Diarmaid MacCulloch, “Thomas Cranmer, A Life”; G.W. Broniley, “Thomas Cranmer, Theologian”.)

¶§:¶

735F Wilmot, John. Earl of Rochester. 1647-1680

Poems, (&c.) on several occasions: with Valentinian: a tragedy. Written by the right honourable John late earl of Rochester.

London: Printed for Jacob Tonson, 1696 $6,600

Octavo, 11 x 17.5 cm. Second edition. A8,a8, B-R8

The spine has been rebacked with the original boards so the binding is tight and secure throughout, and bound with new endpapers. A previous owner has written his name several times throughout but this does not affect the text and indeed adds to the book. The pages are clean, if browned. The only flaw is wormholes to the pages’ top margins. These are predominantly from page 200 to the end but with other smaller worming present in the book. There has also been some bookworm damage to the rear board, and this has now been repaired. Needless to say, the worms are long since gone.

“During Rochester’s lifetime only a few of his writings were printed as broadsides or in miscellanies, [Later this week I’ll write about Miscellanies] but many of his works were known widely from manuscript copies, a considerable number of which seem to have existed. ( I do wish I could come apon one of these!) […] In February of 1690/91, Jacob Tonson, the most reputable publisher of the day, produced a volume entitled ‘Poems On Several Occasions.’ The appearance of the author’s name and title on the title-page is significant. It may indicate that this edition was produced with the approval of the Earl’s family and friends, and it is possible that they may have intervened to prevent the publication of Saunders’s projected edition [license obtained from the Stationer’s Company by Saunders in November of 1690, no edition was ever produced]. Tonson’s edition is introduced by a laudatory preface written by Thomas Rymer which states that the book contains ‘such Pieces only, as may be receiv’d in a vertuous Court’ and is therefore to be regarded only as a selection of Rochester’s writings. Nevertheless it contains, in addition to twenty-three genuine poems which had appeared in the [pirated] Antwerp editions of 1680, sixteen others, including some of Rochester’s best lyrics. No spurious material seems to have been admitted to this collection, but there is a possibility that salacious passages may have been toned down to suit the taste of a ‘virtuous Court.’”

“[Wilmot] is one of these English poets who deserve to be called ‘great’ as daring and original explorers of reality; his place is with such memorable spiritual adventurers as Marlowe, Blake, Byron, Wilfred Owen and D. H. Lawrence. Like Byron and Lawrence, he was denounced as licentious, because he was a devastating critic of conventional morality. Alone among the English poets of his day, he perceived the full significance of the intellectual and spiritual crisis of that age. His poetry expresses individual experience in a way that no other poetry does till the time of Blake. It makes us feel what it was like to live in a world which had been suddenly transformed by the scientists into a vast machine governed by mathematical laws, where God has become a remote first cause and man an insignificant ‘reas’ning Engine.’ [See ‘A Satyr Against Mankind] In his time there was beginning the great Augustan attempt to found a new orthodoxy on the Cartesian-Newtonian world-picture, a civilized city of good taste, common sense and reason. Rochester’s achievement was to reject this new orthodoxy at the very outset. He made three attempts to solve the problem of man’s position in the new mathematical universe. The first was the adoption of the ideal of the purely aesthetic hero, the ‘Strephon’ of his lyrics and the brilliant and fascinating Dorimant of Etherege’s comedy. It was a purely selfish ideal of the ethical hero, the disillusioned and penetrating observer of the satires. This ideal was related to truth, but its relationship was purely negative. The third was the ideal of the religious hero, who bore a positive relation to truth. This was the hero who rejected the ‘Fools-Coat’ of the world and lived by an absolute passion for reality. In his short life Rochester may be said to have anticipated the Augustan Age and the Romantic Movement and passed beyond both. In the history of English thought his poetry is an event of the highest significance. Much of it remains alive in its own right in the twentieth century, because it is what D.H. Lawrence called ‘poetry of this immediate present, instant poetry … the soul and the mind and body surging at once, nothing left out.” (Quoted from Vivian de Sola Pinto’s edition of Wilmot’s Poems published by ‘The Muses Library’)

Wing 1757; Prinz XIV;Grolier’s Wither to Prior #987; O’Donnell A 16 (Prologue), BB 4.1c.

September 29, 2021 at 6:04 PM

Greetings, James, trust all’s well there. Time & patience permitting, please: (1) Can you send me any information on the Bear image (printer’s mark?), your Cooper time? And, (2) Re your enviable copy of Ld Rochester’s POEMS, a book I know rather well by now, who’s the previous owner you mentioned, whose signature appears a few times in this copy? All good wishes, sorry to burden you, MEM ___