EROTOMANIA, OR A TREATISE DISCOURSING OF THE ESSENCE, CAUSES, SYMPTOMES, PROGNOSTICKS, AND CURE OF LOVE, OR EROTIQUE MELANCHOLY.

(Oxford: Printed by L. Lichfield, 1640). $9,500

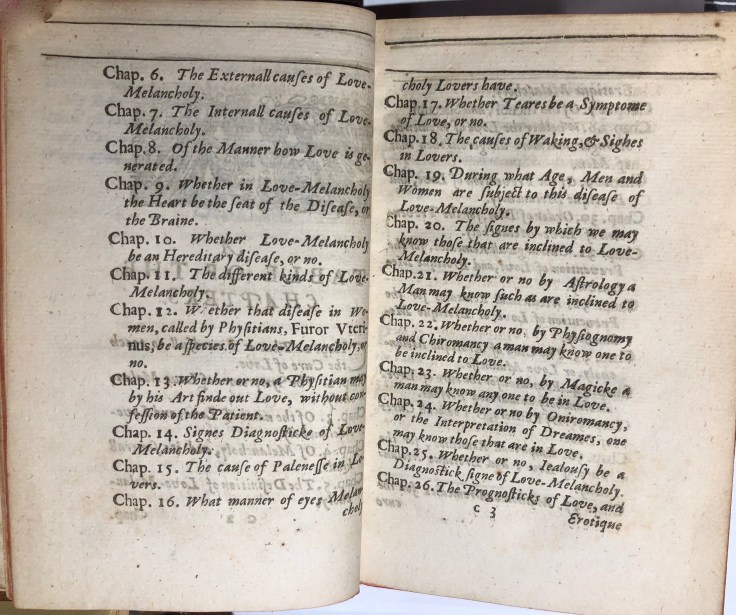

SMALL OCTAVO (5 3/4 x 3 5/8″). a-b⁸ c⁴ A-Z⁸.. Translated from the French by Edmund Chilmead. FIRST EDITION IN ENGLISH. This copy is neatly bound in 19th century calf with a gilt spine. it is quite a lovely copy.

SMALL OCTAVO (5 3/4 x 3 5/8″). a-b⁸ c⁴ A-Z⁸.. Translated from the French by Edmund Chilmead. FIRST EDITION IN ENGLISH. This copy is neatly bound in 19th century calf with a gilt spine. it is quite a lovely copy.

First some symptoms:

“pale and wan complexion, joined by a slow fever … palpitations of the heart, swelling of the face, depraved appetite, a sense of grief, sighing, causeless tears, irresistible hunger, raging thirst, fainting, oppression, suffocation, insomnia, headaches, melancholy, epilepsy, madness, uterine fury, satyriasis, and other pernicious symptoms …”

This book is filled with details chosen on account of the personal motives and life ex- perience of the author. A close reading of Ferrand’s treatise (in particular a careful comparison of the two editions) reveals that he had to deal with criticism from both the religious establishment (the Catholic Church) and the academic establishment (his colleagues in the Paris medical faculty)

“Climate, diet and physical activity (three of the six “non-natural  causes”) were the main elements controlling an individual’s health8. However, a reading of descriptions of the lifestyle which is most likely to lead to being infected by love melancholy makes it clear that the disease was characteristic of a specific social class. Wine, white bread, eggs, rich meats (especially white meat and stuffed poultry), nuts and most sweets were thought to be prob- lematic. Aphrodisiac foods such as honey, exotic fruits, cakes and sweet wines were considered to be extremely dangerous.

causes”) were the main elements controlling an individual’s health8. However, a reading of descriptions of the lifestyle which is most likely to lead to being infected by love melancholy makes it clear that the disease was characteristic of a specific social class. Wine, white bread, eggs, rich meats (especially white meat and stuffed poultry), nuts and most sweets were thought to be prob- lematic. Aphrodisiac foods such as honey, exotic fruits, cakes and sweet wines were considered to be extremely dangerous.

A close look at this list reveals a diet available to and typical of only the wealthy, mainly the nobility. Sleeping in a very soft bed was also regarded as very dangerous, since it aroused lust11. Farmers were hardly likely to suffer from this problem. The writers claim that an idle lifestyle that includes excessive dining and minimal physical activity is dangerous for two reasons: first, an idle person wastes his time thinking, which dries the body and makes it melancholic; second, and much worse, idle people indulge in useless activities like plays and dances that involve both men and women and thus induce lust.

“[The disease] is most evident among such as are young and lusty, in the flower of their years, nobly descended, high-fed, such as live idly, and at ease,” writes Burton12. He scorn- fully examines the lifestyle of the nobility, which gives rise to burning desire, and hence to love melancholy. Ferrand, though not as directly critical, em- phasises the same factors and writes that “great lords and ladies are more inclined to this malady than the common people”13. Class difference, formerly only hinted at in the discussion on diet, becomes the major issue. But are young aristocratic men and women, who obviously eat and sleep better than most, more inclined to this disease by reasons of their lifestyle, or is there another cause for their distress?

Having dealt with the various therapeutic techniques, Ferrand declares: “No physician would refuse to someone suffering from erotic mania or melancholy the enjoyment of the object of desire in marriage, in accordance with both divine and human laws, because the wounds of love are cured only by those who made them.”14 Although Ferrand only deals quite briefly with this type of remedy (compared to the dozens of pages he devotes to medical therapies), he is also quite decisive. Only by union with the beloved will the patient be healed completely; but this can be achieved only in accordance with divine and human rules. In his chapter on love melancholy in married couples, Ferrand is obviously fully aware that these rules are in many cases the cause of youthful distress. Acknowledging that marriage is not a guaran- tee against the disease, he admits that love melancholy in married couples is usually the result of the animosity arising in a couple that was forced to marry and consequently sought love outside the marriage bonds”. (Michal Altbauer-Rudnik)

Ferrand declares: “No physician would refuse to someone suffering from erotic mania or melancholy the enjoyment of the object of desire in marriage, in accordance with both divine and human laws, because the wounds of love are cured only by those who made them.” (Love, Madness and Social Order: Love Melancholy in France and England in the Late Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries. Michal Altbauer-Rudnik)

Madan notes that “If Robert Burton was acquainted with the first edition of this book, as he may well have been, there can be little doubt that he has taken or imitated the general method and treatment of the subject, in his Anatomy of Melancholy”. Burton certainly owned a copy of the Paris 1623 edition (N. K. Kiessling, The Library of Robert Burton, Oxford, 1988, no. 566).The Inquisition showed an interest, and tried Ferrand for heresy. Today, the work provides a rare insight into 17th century understandings of anxiety, depression, love relations. Robert Burton devoted more than a third of The Anatomy of Melancholy, published in Oxford in 1621, to a discussion of love melancholy.

HERE THERE IS A reciprocal connection between disease and society; we can trace on the one hand the way the social world shapes the course of an illness and on the other hand the way the symptoms of an illness shape the social world.

References

- The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Spring, 1989), pp. 41-53

- Lydia Kang MD & Nate Pederson. Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything “Bleed Yourself to Bliss” (Workman Publishing Company; 2017)

- Lesel Dawson, Lovesickness and Gender in Early Modern English Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008),

-

Michal Altbauer-Rudnik. Love, Madness and Social Order: Love Melancholy in France and England in the Late Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries (Gesnerus 63 (2006) 33–45)

QUOTED FROM https://parthenissa.wordpress.com

Erotomania

Which brings us to Erotomania. Originally written in French by Jacques Ferrand in 1623, it is a textbook that discusses the diagnosis and treatment of lovesickness. Translated into English in 1640, Erotomania is prefaced by a series of poems by various Christ Church wits. Rather in the tradition of Coryat’s Crudities, these poems are largely performative, a communal university game that ironises the text they preface and which jokingly frame the book itself as a prophylactic. The first poem, by W. Towers, plays on the conceit that the lovesick reader must have made a mistake in buying the volume, that (s)he has picked it up not for medical reasons but has mistaken it for a pleasurable romance: “Thou, that from this Gay Title, look’st no high’r/Then some Don Errant, or his fullsome Squire”. F. Palmer mock-prophesises the world turned on its head: “The World will all turne Stoicks, when they find/This Physick here”… “Men, as in Plagues, from Marriage will be bent/And every day will seem to be in Lent”

Prefatory material aside, Erotomania consists of 39 detailed chapters discussing the treatment of love melancholy from surgical remedies to potions. It’s less of a manual than a quasi-conduct book – there are no diagrams, unlike in Ambroise Paré’s works. The physician must devise remedies that are not just physical but moral. Ferrand declares in his introduction: “My chiefest purpose is, to prescribe some remedies for the prevention of this disease of Love, which those men for the most part are subject unto, that have not the power to governe their desires, and subject them to Reasons Lawes: seeing that this unchast Love proves oftentimes the Author of the greatest Mischiefes that are in the world (p4)

Therapeutic bloodletting, the letting go of a plethora of blood and heat, as much about the control of a patient’s desire and therefore his (usually his) behaviour. In Chapter 38, entitled Chirurgicall Remedies for Love-Melancholy, Ferrand advises: “If the Patient be in good plight of body, fat and corpulent, the first thing wee doe, we must let him bleed, in the Hepatica in the right arme, such a proportionable quantity of blood, as shal be thought convenient both for his disease, complexion, and strength of body…. Phlebotomy makes those that are sad, Merry: appeaseth those that are Angry: and keeps Lovers from running Mad.”

In other words, bloodletting regulates social behaviour. The unruly humoral body must be tamed. Gail Kern Paster’s The Body Embarrassed is the key critical work here; she has brilliantly drawn on Norbert Elias’s theories of the way that violence, bodily functions (including sexual) are ‘civilised’ by ever-increasing thresholds of shame. Paster makes the connection between the disciplining of humoral fluids and the way that the Bakhtinian grotesque and carnivalesque becomes tamed by the classical body. Her study of Middleton’s city comedies and Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar explores the inflections of gender. Anxieties around the ‘leaky vessel’ of the female body, whether through menstruation or urine, underlines the increasing ideological investment in female intactness that becomes a system of control and decorum. (Nowadays the female body is disciplined by the baby diets in Closer magazine and the Daily Mail sidebar of shame. But I digress.)

Leave a Reply