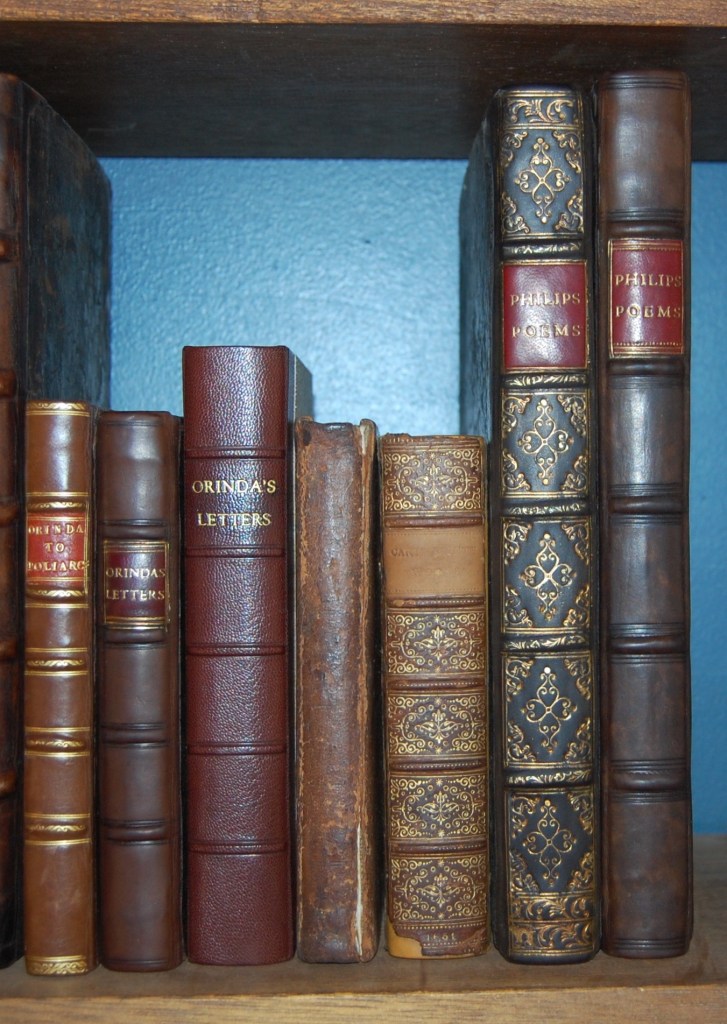

Today, I have seven books by Katherine Philips, A first pirated edition of the Poems, A first Authorized edition of the Poems, a fourth edition of the Poems and three copies of the first edition of the Letters! One of her first publications, a commendatory poem to the 1651 edition of Cartwright’s Poems.

The Unauthorized First Edition

The Unauthorized First Edition

717 G Philips, Katherine (1631-1664)

717 G Philips, Katherine (1631-1664)

Poems. By the incomparable, Mrs. K.P.

London: Printed by J[ohn]. G[rismond]. for Rich. Marriott, at his shop under S. Dunstans Church in Fleet-street, 1664 $SOLD

Octavo: 17 x 11 cm. [14] (of 16), 236, [4], 237-238 (of 242) pp. A-P8, Q8, R4. This copy lacks leaf A1 (imprimatur,) leaf Q7, blank leaf Q8, and the final three leaves (R2-4) which comprise the final leaf of poems, the errata leaf, and the final blank.

THE RARE UNAUTHORIZED FIRST EDITION. This was the only edition published in Philips’ lifetime. Philips’ died of smallpox in June 1664, five months after the appearance of this publication. The first authorized edition did not appear until 1667. Bound in contemporary sheepskin, re-cased. Fine internally.

“In 1664 an unauthorized edition of Philips’s Poems was published; the bookseller Richard Marriott had entered the volume in the Stationers’ register in November 1663 and advertised it for sale in January. Philips, claiming she ‘never writ any line in my life with an intention to have it printed’, expressed her indignation in a number of letters, defending herself against any ‘malicious’ suggestion that she ‘conniv’d at this ugly accident’: ‘I am so Innocent of this pitifull design of a Knave to get a Groat, yt I was never more vex’d at any thing, & yt I utterly disclaim whatever he hath so unhandsomly expos’d’ (Letters, 128, 142). Some twentieth-century critics are sceptical of these conventional disclaimers: the 1664 edition is based on manuscripts that Philips herself circulated among friends (not at all ‘abominably transcrib’d’ and inauthentic, as she claims), and the text of the seventy-five poems it contains differs only slightly from that in the later, authorized edition of 1667. Yet her distress at seeing poems she considered private, circulated within a literary community of intimate friends, exposed to public gaze, goes beyond the conventional:‘Tis only I … that cannot so much as think in private, that must have my imaginations rifled and exposed to play the Mountebanks, and dance upon the Ropes to entertain all the rabble’ (Ibid. 129–30).”(Warren Chernaik, ODNB)

This is perhaps the most famous English collection of poems by a woman prior to 1700. P.W. Souers, in his critical biography of Katherine Philips, asserts for her the right to be historically the first English poetess—“In her, for the first time in the history of English letters, a woman was received into the select company of poets.” Jeremy Taylor dedicated to her his “Discourse on the Nature, Offices, and Measures of Friendship;” Abraham Cowley, Henry Vaughan the Silurist, Thomas Flatman, the Earl of Roscommon, and the Earl of Cork and Orrery all celebrated her talent, and Dryden could pay no higher compliment to Anne Killigrew than to compare her to Orinda.

Wing (CD-Rom, 1996), P2032

718G Katherine Philips

Poems By the most deservedly Admired Mrs. Katherine Philips The Matchless Orinda. To which is added Monsieur Corneille’s Pompey & Horace,} Tragedies. With several other Translations out of French.

London: Printed by J. M. for H. Herringman, 1667 SOLD

Folio 7 X 11 1/4 inches π2, A2, a-f2, B-Z2, Aa-Zz2, Aaa-Zzz2, Aaaa-Mmmm2. (Final leaf blank and original).

First sanctioned edition, enlarged, preceded by a pirated and suppressed edition of 1664 ( see Above). This copy is bound in contemporary boards, which have been recently rebacked with a gilt spine . On the center of both boards are the arms of Sir Robert Vyner (1631-1688)Lord mayor of London. In 1674 Viner was elected lord mayor; the pageant on that occasion, which was witnessed by the king and queen, appears to have been more than usually magnificent. Elkanah Settle, the city poet, composed the verses, and the whole was produced at the cost of the Goldsmiths’ Company  It is Interesting that he owned this book before he was Lord Mayor.

It is Interesting that he owned this book before he was Lord Mayor.

Philips was “the daughter of a London merchant, Katherine Fowler [her maiden name] was probably the first English woman poet to have her work published. She married a gentleman of substance from Cardigan, James Philips, and seems to have moved effortlessly into the literary circle adorned by Vaughan, Cowley, and Jeremy Taylor. She was best known by her pseudonym ‘Orinda’ and the name appears on the collection of her Letters, which give a useful picture of the early seventeenth-century literary world. Her translation of Corneille’s ‘Pompee’ was performed in Dublin in 1663 and a collection of her verses was published posthumously in 1664.” (Stapleton)Mrs. Philips’ poems were circulated in manuscript, and secured for her a  considerable reputation. The surreptitious quarto edition produced in 1664 caused her much annoyance, and …Some trouble was taken, it would appear, to destroy the copies, which would account for its rarity.

considerable reputation. The surreptitious quarto edition produced in 1664 caused her much annoyance, and …Some trouble was taken, it would appear, to destroy the copies, which would account for its rarity.

In the preface of this 1667 edition, reference is made to the ‘false edition,’ and a long letter from the author in relation to it is quoted..

Wing P-2033; Hayward 116; Grolier 669; CBEL II, 480; Sweeney 3460.

A large copy of the Fourth Edition

719G Katherine Philips 1631-1664

Poems By the most deservedly Admired Mrs. Katherine Philips, The Matchless Orinda. To which is added Monsieur Corneilles Pompey & Horace,} Tragedies. With several other Translations out of French.

London: Printed by T.N. for Henry Herringman , 1678 SOLD

Folio 6 3/4 11 inches Fourth edition. [ ]2, A4, a-Z4, Aa-Tt4, Uu2.

This copy is in good condition internally. It is bound in full seventeenth century English calfskin, It has a blind stamped panel with stylized tulip ornaments in the corners , this too was signed ( the initials “IoW” are incorporated in the design)

This copy also has ownership declarations and a book plate from the Prujean family. It was a gift from Mrs.Francis Prujean (Her book plate is here) to Ann Prujean 1682.

Two Copies of Katherine Philips Letters.

103G Katherine Philips

Letters from Orinda to Poliarchus

London: printed by W.B. for Bernard Lintott, 1705 $5500

Octavo 6 3/4 X 3 3/4 inches A-R8 First edition. This copy is bound in original full calf stored in a custom morocco case.

This is a collection of 48 ( XLVIII) actual letters written by Philips to her patron Sir Charles Cotterell published several decades after her death, there is quit a bit of discussion of the

literary culture of the seventh century in Britain. Including incite to Philips writing and reading habits. she often mentions books she is reading and plays which she is working on.Philips was interested in the epistolary form, she founded the Society of Friendship in 1651 until 1661 was a semi-literary correspondence circle made up of mostly women, though men were also involved. The membership of this group, however, is somewhat questionable, because the authors took on pseudonyms from Classical literature (for example Katherine took on the name Orinda, in which the other members added on the accolade “Matchless.”) It is interesting to see the relations between the female members of the circle, especially Anne Owen, who is known in Philips’s poems as Lucasia. Half of Katherine’s poetry is dedicated to this woman. Anne and Katherine seem to have been lovers in an emotional, if not in a physical, sense for about ten years. Also significant as correspondents and lovers were Mary Awbrey (Rosania) and Elizabeth Boyle (Celimena). Elizabeth’s relationship with Katherine, however, was cut short by Philips’ death in 1664.In “The Sapphic-Platonics of Katherine Philips, 1632-1664” Harriette AndreadisSource:Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 15, no. 1 (autumn 1989): 34-60.Ms Andreadis, in this essay nicely gives a view of Orinda’s life (and Loves) in relation to her writing by using excerpts from her poems and These letters;

Another copy of the above, with a rebacked binding, same collation.

767G Katherine Philips

Letters from Orinda to Poliarchus

London: printed by W.B. for Bernard Lintott, 1705 $3,500

One of Philips’ early publications, a commendatory poem to the 1651 edition of Cartwright’s Poems.

117F William Cartwright 1611-1643

Comedies, Tragi-Comedies, With other Poems by Mr. William Cartwright late Student of Christ–Church in Oxford and Proctor of the University. The Ayres and Songs set by Mr. Henry Lawes Servant to His late Majesty in His Publick and Private Musick. —nec Ignes, Nec potuit Ferrum,—

London: Printed for Humphrey Moseley, and are to be sold at his Shop, at the sign of the Prince’s Arms in St Pauls Church–yard, 1651 $3,750

Octavo 4 1/4 X 6.1/2 inches. [Portrait]1, [a]-b8, *14 , *8, ¶4, **8, ***14, *10, a-e8, f4, g-k8, A-T8, U3, U8, X2, with leaf *11 in cancelled state as usual and showing the original stub. Leaves **7 and U1-3 appear to be in uncancelled state with no evidence of stubs, otherwise this collation matches that described by Evans. First edition.

This copy is bound in modern butterscotch calf with a gilt spine, in period style.It is quite a nice copy. “Cartwright enjoyed a considerable success among his contemporaries but posterity has been less kind and his work is only known to students of seventeenth century literature. He was educated at Westminster School and went up to Christ Church, Oxford, in 1628; he spent the rest of his short life there. He wrote four plays, intended for academic performance: The Ordinary or The City Cozener (1634) shows clearly the influence of Ben Jonson; The Lady Errant, The Royall Slave, and The Siege or Love’s Convert were published in 1651. The Royall Slave, with designs by Inigo Jones and music by Henry Lawes, was acted for King Charles I and Henrietta Maria at Oxford in 1636 and proved a great success. Cartwright took holy orders in 1638 and wrote no more plays but he became a celebrated preacher; in 1642 he became reader in metaphysics to the university. A Royalist, Cartwright preached at Oxford before the king after the Battle of Edgehill. The edition of his works published in 1651 contained 51 commendatory verses by writers of the day, including Izaak Walton and Henry Vaughan. The Plays and Poems of William Cartwright were collected and edited by G. Blakemore Evans and published in 1951. (Stapleton) This work also includes the first poem by Katherine Phillips to be printed (DNB). Cartwright was well liked, and many of his wide circle of friends contributed to the verses occupying the first 100 pages or so; Dr. John Fell, Jasper Mayne, Henry Vaughan the Silurist, Alexander Brome, Izaak Walton, Francis Vaughan, Thomas Vaughan, Henry Lawes, Sir John Birkenhead, James Howell and many others. Wing C-709; see also The Plays and Poems of William Cartwright by G. Blakemore Evans, pages 62-72; Hayward English Poetry Catalogue, 104; Greg page 1027.

Philological Quarterly

“That Private Shade, Wherein My Muse Was Bred”: Katherine Philips and the Poetic Spaces of Welsh Retirement

By Prescott, Sarah

Article excerpt

Katherine Philips’s literary career provides the scholar with the most extensive surviving example of women’s manuscript circulation and coterie poetic practice in the seventeenth century. (1) Both in her own lifetime and posthumously, Philips was lauded in terms of her virtuous image as “the matchless Orinda” and then increasingly noted in terms of her pivotal role in the poetic “Society of Friendship,” a Royalist coterie she created in the 1650s. Modern critical attention likewise focused on her poetry of female friendship and her place as a role model for later women writers. (2) More recently, however, Philips has been seen as a political poet whose work should be read in the context of her Royalist sympathies. As a result, what was previously considered to be Philips’s gendered retreat into a “private” poetic world of like-minded literary friends is instead recognized as a characteristic articulation of encoded Royalist allegiance. (3) As Hero Chalmers phrases it, in Philips’s work “depictions of feminine withdrawal reflect the Interregnum royalist need to represent the space of retirement or interiority as the actual centre of power” (4) What is rarely taken into account is not only that Katherine Philips wrote most of her poetry in Wales, but that she is the only known Anglophone woman poet writing from Wales in the entire seventeenth century. In addition, a fair proportion of her work is not addressed to the members of her “Society of Friendship” but to an audience of readers and acquaintances within Wales itself. (5) This body of occasional and elegiac poetry is rarely mentioned in studies of Philips’s writing.(6) In contrast, this essay makes Katherine Philips’s relation to Wales the center of its investigation. To reframe Chalmers’s insight above, I will ask in what ways an attention to the geographical spaces of retirement Philips inhabited as a writer shift our understanding of her work and her significance in literary history, specifically Welsh literary history. On a more detailed textual level, I will ask how these “material” spaces inform the “discursive” spaces of her poetry. Although Philips’s experience of Wales was expressed in a number of different ways in her poetry and letters, here I focus on a selection of her poems which explore the theme of retirement in relation to her Welsh context: “That private shade, wherein my Muse was bred.” (7)

My approach builds on recent developments in the study of women’s writing which look beyond England and consider women’s writing in Britain across the early modern archipelago. (8) Despite the rise of “archipelagic” literary studies of Britain more generally, the perceived need to be inclusively British in our approach to literary history has taken longer to establish itself as a key component in the history of women’s writing. (9) One way forward is to put more emphasis on the different places from which women produced literary texts and to pay more attention to the way in which different locations and sites of literary production shaped the content of these texts. Kate Chedgzoy has argued that “when we study early modern English women’s writing, we need to pay more attention to texts in the English language produced in Wales, Scotland, Ireland, British North America and the Caribbean as well as England. And we need to do so in the context of new geographies of that changing world that enable us to grasp the full complexity of the locations the writing comes from, and how and why that locatedness matters.” (10) Furthermore, as Chedgzoy suggests, we also need to make “an effort to learn more about the ways in which women perceived themselves as Irish, Scots, Welsh, English and/or British.” (11)

From this perspective, Philips, a writer whose career was based in Wales and latterly Ireland, can be read not as the archetypal English coterie writer but rather as representatively archipelagic. As Chedgzoy has noted further, “a properly internationalist, Atlantic and comparative approach to early modern British women’s writing” might include, for example, “Katherine Philips’s translations of French plays, made in Wales and performed in Ireland. …

March 7, 2016 at 1:12 PM

Reblogged this on jamesgray2.