|

Tonight I’ll begin now, where I am or rather what i’m (re) Reading again and again.. By William Gass is one of my favorite books, “This small but memorable treatise, written “for all who live in the country of the blue,” examines the color as state of mind, as Platonic Ideal, as a notoriously erotic hue, and as a color of our interior life. In a brilliant, extended meditation, Gass mulls over blue in literature and art, dance, music, and the popular press. No shade or variation escapes his engaged and engaging prose or his vertiginous asides. This is a witty, lyrical, highly original, and beautifully written book that demands to be read and redefines the meaning of a “philosophical inquiry.””Not since Herman Melville pondered the whiteness of Moby Dick has a region of the spectrum been subjected to such eclectic scrutiny. . . Gass gives philosophy back its good old name as a feast that can never sate the mind.”

I read it probably in 1980 or 81 and it lead me to Robert Burtons’ The Anatomy of Melancholy. Not having read much 17th century prose at that time, I was so excited, ” the 17th century IS POST MODERN!!” I exCLAIMED to Jean Howard, my professor of 17th century literature… and here is why:::: “Il n’y a pas de hors-texte” quote Derrida!Burton destabilizes Psychology it self 300 years before Lacan castrates Freud!

Burton is by no means a stable ‘Traditional’ Solid subject author, He questions every single criterion of legitimation he encounters, In fact He hovers between reader ,author, editor and critic so ethereally that it is hard to tell if he is on his way to take us out of our own subjective reading at every turn. Does not Burton inaugurate The crisis identified in Jean-François Lyotard The Postmodern Condition a crisis in the “discourses of the Human Sciences” ? MELANCHOLY IS “That Dangerous Supplement…” which brings us to face the death drive, or the absolute destruktion (of Heidegger)Ah Ha! this is where Wm Gass gets his license to say “Still, we permit the appearance of our meats, sauces, fruits, and vdgetables to dominate our tongues until it is difficult to divide a twist of lemon or squeeze of lime from the colors of their rinds or separate yellow from its yolk or chocolate from the quenchless brown which seems to be the root, shoot, stalk, and bloom of it. Yet I hardly think the eggplant’s taste is as purple as its skin. In fact, there are few flavors at the violet end, odors either, for the acrid smell of blue smoke is deceiving, as is the tooth of the plum, though there may be just a hint of blue in the higher sauces. Perceptions are always profound, associations deceiving. No watermelon tastes red. Apropos: while waiting for a bus once, I saw open down the arm of a midfat, midlife, freckled woman, suitcase tugging at her hand like a small boy needing to pee, a deep blue crack as wide as any in a Roquefort. Split like paper tearing. She said nothing. Stood. Blue bubbled up in the opening like tar. One thing is certain: a cool flute blue tastes like deep well water drunk from a cup.” But On Being Blue ends too fast it is 91 pages of wonder, But next to Burton and his 723 pages, Gass is an Apéritifs to Burton’s Cask! It is a book everyone should look at! I know that there is an etiquette to Blogging, but I don’t know it (yet maybe) In any case I will go on too long about this book or maybe not, It deserves far more that i can say, write, gesticulate, or quote about… Nicholas Lezard writes:The book to end all booksNicholas Lezard celebrates The Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton, a 17th-century compendium of human thought that is funnier than it sounds “it is not just Burton’s thoughts on the subject of melancholy, but the thoughts of everyone who had ever thought about it, or about other things, whether that be goblins, beauty, the geography of America, digestion, the passions, drink, kissing, jealousy, or scholarship. Burton, you suspect, felt the miseries of scholars keenly. “To say truth, ’tis the common fortune of most scholars to be servile and poor, to complain pitifully, and lay open their wants to their respective patrons… and… for hope of gain to lie, flatter, and with hyperbolical elogiums and commendations to magnify and extol an illiterate unworthy idiot for his excellent virtues, whom they should rather, as Machiavel observes, vilify and rail at downright for his most notorious villainies and vices.” And that’s a good quote to be getting on with: it shows you that Burton is on the side of the angels, that he’s prepared to stick his neck out, and that he is funny.” |

The Anatomy of Melancholy

Robert Burton, introduction by William H. Gass

One of the major documents of modern European civilization, Robert Burton’s astounding compendium, a survey of melancholy in all its myriad forms, has invited nothing but superlatives since its publication in the seventeenth century. Lewellyn Powys called it “the greatest work of prose of the greatest period of English prose-writing,” while the celebrated surgeon William Osler declared it the greatest of medical treatises. And Dr. Johnson, Boswell reports, said it was the only book that he rose early in the morning to read with pleasure. In this surprisingly compact and elegant new edition, Burton’s spectacular verbal labyrinth is sure to delight, instruct, and divert today’s readers as much as it has those of the past four centuries.

All I can say is that most modern books weary me, but Burton never does…His writing is like talk, learned but earthy, and once he starts, he is hard to stop…That he was a humorist in our sense of the word we need no biographical facts to attest: The Anatomy of Melancholy is, by a magnificent and somehow very English irony, one of the great comic works of the world. — Anthony Burgess

No prose writer—ever—has been more of a universe than Robert Burton, self-curing author of The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), an essay on the humors that went utterly out of control and became the craziest, best entertainment ever written in English—far more important than the King James Bible in terms of effect on alpha—class letters. — William Monahan, Bookforum

319G Burton, Robert. 1577-1640

319G Burton, Robert. 1577-1640

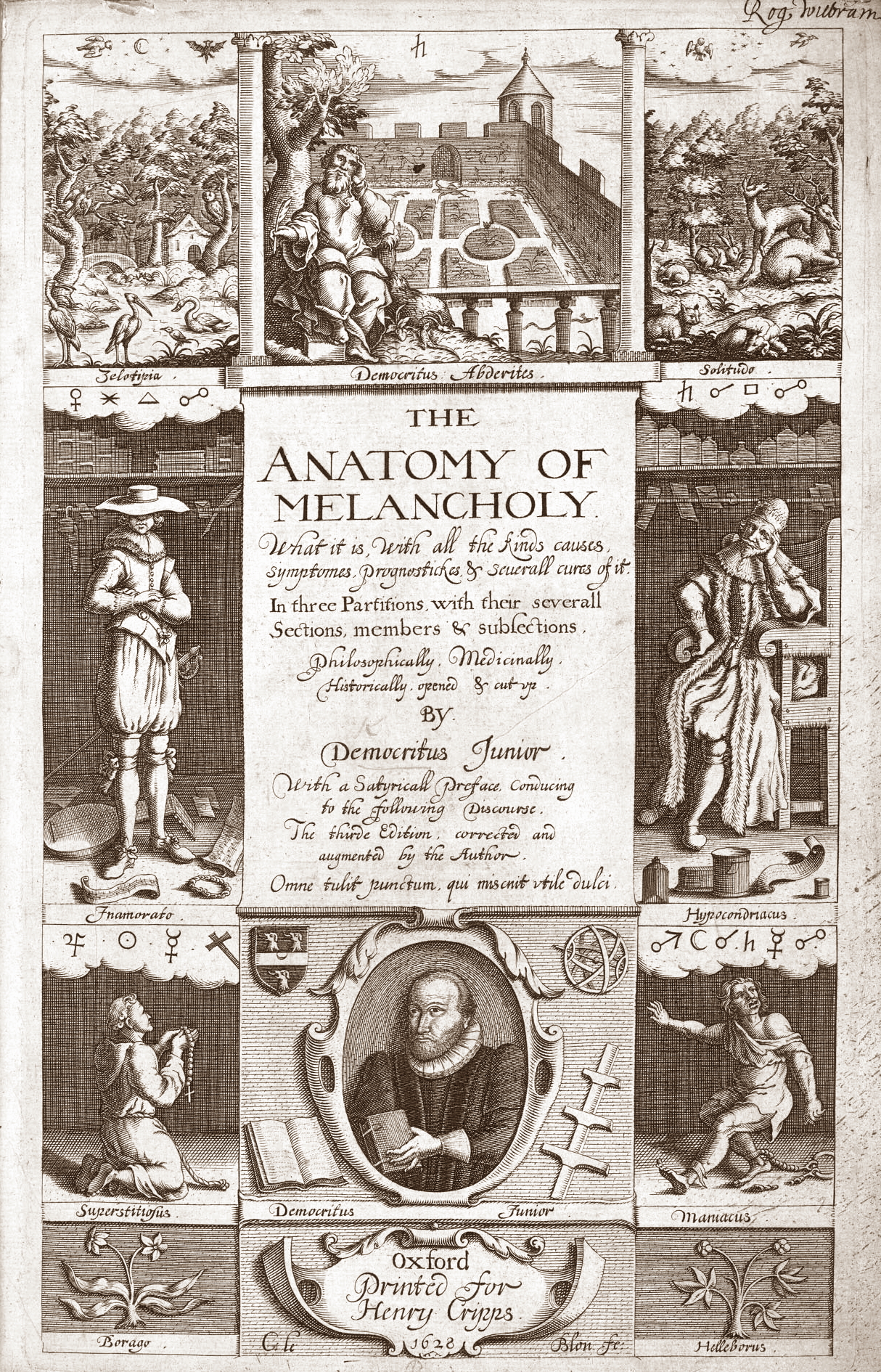

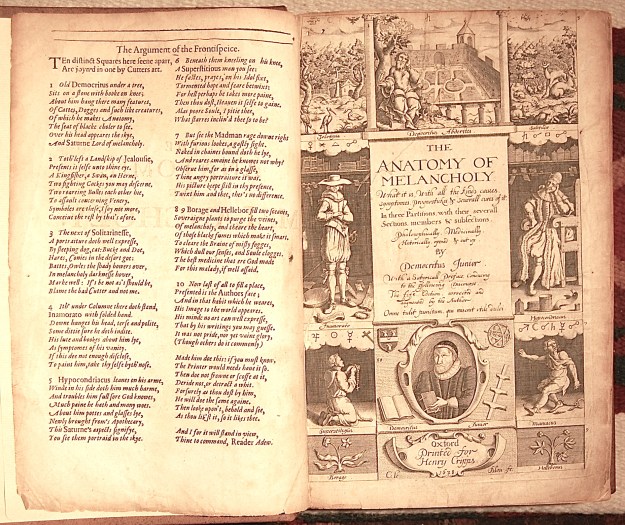

The Anatomy of Melancholy. What it is, with all the kinds, causes, symptomes, prognostickes, & severall cures of it. In three Partitions, with their severall Sections, members & subsections. Philosophicaly, Medicinally, Historically opened & cut. By Democritus Junior. With a Satyricall Preface conducing to the following Discourse. The fift Edition, corrected and augmented by the Author. Omne tulit punctum qui miscrit utile dulci.

Oxford: L. Lichfield for H. Cripps, 1638 $5,500

Folio, 11 x 7.2 inches. Fifth edition. [π]3, §2, A-K4, A-R4, S6, T-Z4, Aa-Hh4, Ii6, Kk4-Zz4, Aaaa-Eeee4, Ffff2, Gggg-Zzzz4, Aaaaa4.

This edition has the charming pictorial engraved title-page by C. Le Blon, which depicts types of melancholy. The edition also contains the “Argument of the frontispiece” leaf, quite often lacking. This copy is bound in modern full calf, . Some very light browning, occasional spotting, but overall a really nice copy with ample margins.

Burton’s classic study of depression, The Anatomy of Melancholy, “has been more frequently reprinted than almost any other psychiatric text, appearing in over seventy editions since its original publication. Burton believed depression to be both a physical and spiritual ailment. Prompted by his own bouts with the affliction, he employed his considerable erudition and wit to write what amounts to the first psychiatric encyclopedia, citing nearly 500 medical authors in the course of classifying the myriad causes, forms and symptoms of depression, and describing its various cures. The work is also a literary tour-de-force in the tradition of Renaissance paradoxical literature.” (Norman)

“Burton had read much, and all that he had read, or nearly all, was refined and incorporated into The Anatomy. The whole book is elaborately divided and subdivided into partitions, divisions, sections, members and sub-sections. The first partition is devoted to the definition of his subject and its species and kinds, the causes of it, and—at length—the symptoms: ‘for the Tower of Babel never yielded such confusion of Tongues as the Chaos of Melancholy doth of Symptoms.’ The second deals with the cure, and Burton’s demonstration that it is necessary to live in the right part of the world to avoid melancholy occasions a long digression: a delightful account of foreign lands based—for Burton never travelled—on a wide reading of the cosmographers, and a powerful advocacy of the delights of country life. The third part deals with the more frivolous kinds of melancholy and the fourth with the serious, Religious Melancholy, with some moving reflections on the ‘Cure of Despair.’ The Anatomy was one of the most popular books of the seventeenth century. All the learning of the age as well as its humour—and its pedantry—are there.” (Printing & the Mind of Man)

As Osler notes, “this edition has the distinction – possibly unique for any book – of having been printed piecemeal in three cities.” According to Madan, pages 1-346 were actually printed at Edinburgh but that the Scottish edition was suppressed at the insistence of the Oxford printers, who then agreed to incorporate the pirated pages in the present edition; some 68 leaves, incorporating Burton’s latest changes, were actually reprinted in London. For an account of the printing history of this edition see further Oxford Bib. Soc. Proceedings & Papers I (1922-6), pp. 194-7.

Garrison-Morton 4908.1; Grolier, English, 18; Hunter & Macalpine, pp. 94-99; Jordan-Smith 5; STC 4163; Madan, Oxford books II # 881.

“Melancholy, the subject of our present discourse, is either in disposition or in habit. In disposition, is that transitory Melancholy which goes and comes upon every small occasion of sorrow, need, sickness, trouble, fear, grief, passion, or perturbation of the mind, any manner of care, discontent, or thought, which causes anguish, dulness, heaviness and vexation of spirit, any ways opposite to pleasure, mirth, joy, delight, causing forwardness in us, or a dislike. In which equivocal and improper sense, we call him melancholy, that is dull, sad, sour, lumpish, ill-disposed, solitary, any way moved, or displeased. And from these melancholy dispositions no man living is free, no Stoick, none so wise, none so happy, none so patient, so generous, so godly, so divine, that can vindicate himself; so well-composed, but more or less, some time or other, he feels the smart of it. Melancholy in this sense is the character of Mortality… This Melancholy of which we are to treat, is a habit, a serious ailment, a settled humour, as Aurelianus and others call it, not errant, but fixed: and as it was long increasing, so, now being (pleasant or painful) grown to a habit, it will hardly be removed.”

Further a great proximity to The anatomy::;

By http://drvitelli.typepad.com/providentia/2011/03/burtons-melancholy.html

Burton’s Melancholy

It’s hard to imagine from that unwieldy title page that the book published by Robert Burton in 1621 would become a revolutionary best-seller. Divided into three parts, The Anatomy of Melancholy was intended to provide a serious overview of a subject that had been largely neglected up to that time. In his book, Burton avoided providing a precise definition of melancholy (depression) which he felt would “exceed the power of man”. He also stated that “the letters of the alphabet makes no more variety of words in divers languages” than the various symptoms that melancholy could produce in serious sufferers. He considered melancholy to be a universal illness (“Who is free from melancholy? Who is not touched more or less in habit or disposition?” No man living is wholly free, no stoic, none so wise, none so happy, none so patient, so generous, so godly, so divine that he does not at some time or other experience its transitory forms. No other misery is so widespread”).

Robert Burton was certainly qualified to write the book. Born in Leicestershire in 1577, he studied at Christ Church, Oxford and was appointed a vicar in 1616. Despite having a diverse range of interests, including mathematics and astrology, he also devoted much of his time to the serious study of melancholy. By all accounts, Robert Burton suffered from frequent episodes of lifelong depression although actual clinical details are lacking. Hewas one of nine children and his early childhood was apparently an unhappy one. There also seems to be a family history of melancholy as well since his uncle, Anthony Faunt, died following a “passion of melancholy” in 1588. Despite being a brilliant student, Burton’s academic career was marked by long periods during which his studies were interrupted. He finally graduated from Christ Church at the age of twenty-six (nineteen or twenty would have been more typical). Although the gaps in his education are unaccounted for, his lifelong depression seems to be the most obvious explanation.

There is still little known about Burton’s private life aside from a few anecdotal accounts. He never married and he socialized infrequently although he spent his entire academic life at Oxford. While he was frequently depressed, he was also known as “very merry, facete, and juvenile,” and a person of “great honesty, plain dealing, and charity.” He also loved gardening as well as reading in his chambers at Oxford which were “sweetened with the smell of jupiter (incense)” While he hardly ever travelled, he was an avid cartographer and, in virtual fashion, explored much of the world. Despite being a scholar his entire life, Burton was extremely cynical about his fellow academics and academia in general. His reclusive nature didn’t prevent him from being well-regarded by his colleagues and he received prestigious appointments to vicar positions at Oxford and Leicester. Burton also published various Latin verses as well as works in mathematics and a satirical play in when which was well received when it was produced in 1617.

It was The Anatomy of Melancholy which made Robert Burton a success though. Written when the author was in his late forties, the book had a boisterous tone which antagonized many critics (one of whom dismissed it as “an enormous labyrinthine joke”). Serious reviewers were also likely put off by the “phantastical title” which Burton had included to attract “silly passengers that will not look at a judicious piece”. Beginning with the “satyical preface” that vigourously attacked many of the prevailing views on melancholy, the book quickly led into discussing the topic in earnest. The first part of the book was dedicated to discussing the causes, symptoms, and prognosis of melancholy, the second part was dedicated to treatment, and the third part focused on the melancholy often associated with love or religion. Filled with an astounding number of anecdotes and quotations (including quotations by hundreds of medical writers, theologians, classical writers, historians, and poets) , readers of the book often found Burton’s reasoning to be hard to fathom (I certainly did). It likely doesn’t help that up to a fifth of the book is in Latin and Burton also used numerous obscure terms that often mystify modern readers (including words like “stramineous”, “obtretration”, and “amphibological”).

Burton’s theories on melancholy reflected much of the prevailing medical thinking of the time. Along with attributing the disease to an excess of “black bile” (humour theories were popular at the time), he also suggested that melancholy could be linked to heredity, lack of affection in childhood, and sexual frustration. Although it was a more credulous era (witches were still being executed for cursing people into madness), Burton avoided supernatural explanations for melancholy. That’s not to say that he didn’t have his own personal biases though. He was openly misogynistic and frequently denounced women in general and their “unnatural, insatiable lust” in particular. Many of his anecdotes focused on the melancholy caused by men pursuing women, material pleasures, and worldly success although he was more cynical than puritanical. Burton freely admitted that his motivation in writing the book stemmed from his own need to “write of melancholy, by being busy to avoid melancholy. There is no greater cause of melancholy than idleness, no greater cure than business”.

He originally published the book under the pseudonym of Democritus Junior (Democritus being his favourite Greek philosopher) but Burton’s true identity became known soon enough. The odd mixture of scholarship, humour, and medical insights was virtually unprecedented in an academic book andAnatomy quickly became one of the most popular books of that era. Despite the fame and wealth that his book brought to him, Burton’s lifelong melancholy didn’t seem any more manageable as a result. When he died on January 25, 1640, there were widespread rumours that he had hanged himself in his rooms at Oxford. Given that Burton had often predicted that he would die when he reached the age of sixty-three, there may be some truth to the rumour. Considering the harsh punishment for suicidesduring that time (including being buried at a crossroad with a stake through the heart in extreme cases),to the suicide of a prominent Oxford scholar would have likely been carefully concealed. Robert Burton was buried in Christ Church cathedral with full honours. Following Burton’s own instructions, his grave was mared with the following inscription carved under his bust: Paucis Notus Paucioribus Ignotus Hic lacet DEMOCRITUS IUNIOR Cui Vitam Dedit et Mortem Melancholia (“Known to few, unknown to fewer, here lies Democritus Junior, to whom melancholy gave both life and death”). That the inscription helped reinforce the suicide rumour may well have been unintentional.

Burton’s vast collection of books (more than a thousand volumes) was left to the Oxford University library but it was The Anatomy of Melancholy that was his most lasting contribution. Although the book fell into neglect just a few decades after Burton’s death, it was frequently cited by later authors – including Samuel Johnson, John Milton, and Laurence Sterne – and came back into popularity by the beginning of the 19th century. Not only is it considered to be one of the great works of English literature, but it was also one of the first true classics of abnormal psychology. Digging through Burton’s book may not provide the modern student of psychology with much insight into depression but Robert Burton was definitely a pioneer in his own right.

Link to Anatomy of Melancholy (Project Gutenberg)

April 20, 2013 at 5:25 PM

Great stuff, Jim! Bravo!

May 16, 2013 at 3:27 PM

Many thanks for [re]introducing us to this marvellous book!

A teacher at my school introduced us [or was it that the Everyman edition stood out on his wellstocked shelves?]

[ My Everyman is longlost so I want a replacement!]

The A of M inspired Holbrook Jackson’s Anatomy of Bibliomania

September 29, 2015 at 3:58 PM

Reblogged this on jamesgray2 and commented:

This copy will be in my October Fascicule VI